INTERVIEW ARCHIVE

Herald (1994)

Scotland On Sunday (1996)

Journal (2000)

Herald & Post (2000)

Guardian (2001)

Evening Chronicle (2006)

Northern Echo (2006)

Independent on Sunday (2006)

Scotsman (2008)

Q&As

Catherine Lockerbie. The Herald (Glasgow). December 1, 1994.

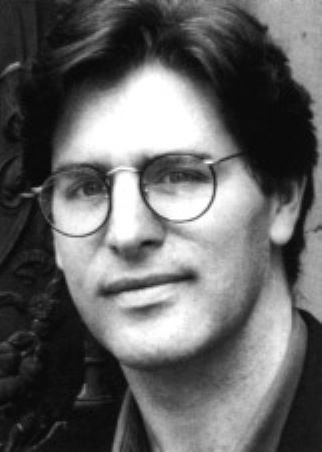

There's something indecently attractive about the Crumeys; crumby they are not. (The name is pronounced Croomey, as they are doubtless weary of pointing out.) Dr Andrew Crumey has magazine male model looks; a post-doctoral degree in non-linear dynamics; and now a prestigious award for Best First Scottish Book Of The Year.

His wife has magazine female model looks, and a sultry Greek accent to match; his three-month old baby could grace many a Pampers commercial and snuggled all the way through the lengthy Saltire and McVitie ceremony, only squawking at a perfectly appropriate moment of a description of the travails of womanhood.

Dr Crumey, born in Glasgow in 1961 and now teaching maths in Newcastle, is hardly heard of in his native country; it is precisely as yet unestablished writers that the Saltire First Book Of The Year was created to encourage. One of its most distinguished recent recipients is A.L. Kennedy, now feted as the best writer of her generation. Janice Galloway too was shortlisted in her time.

There's nothing overtly Scottish about Crumey's novel, Music, In A Foreign Language (Dedalus); it belongs to a more European or Latin American school, all shifting narratives and post-modern self-reflection. We might though wish to brag that there is something overtly Scottish, pertaining to our noble if swiftly diminishing tradition of lads o' pairts, in the fact that a physicist and mathematician has written an award-winning novel.

He points out that his Calvino-esque tale of a narrator picking his way through a post-communist police state and exploring all manner of simultaneous possibilities draws directly on his background in the theoretical physics he studied at St Andrews University.

"In quantum mechanics, you're dealing with probability; you learn that you can never say anything with precision. I've always been interested in the big, philosophical ideas; but as you get deeper into scientific research you become preoccupied with tiny detail and tend to lose the bigger picture. So I thought I would try to regain that via literature."

Citing Borges and Kundera as well as Italo Calvino as influences, he explains that Robert Louis Stevenson — greatly admired by Borges — functioned as an equally important role model. "He was writing in a world context; there's always been a strong tradition of European writing in English."

The Scottish-based literati are in fine fettle right now; it's excellent though to hear in addition a different kind of voice from beyond our habitual mental borders.

Rosemary Goring. Scotland on Sunday. April 7, 1996.

A man in a donkey-brown overcoat sits in the concourse at Waverley station reading Private Eye. It's pure chance that he's there. If his grandfather's bike hadn't punctured one day forcing him to go to the nearest farmhouse for water he wouldn't have met his wife-to-be. The man in the overcoat would never have come to life, and there'd be one more empty seat in the station for pigeons to colonise. Equally, once he was conceived, he might as easily have become a fishmonger as one of Britain's few postmodernist novelists.

These are the kinds of thoughts that occupy Andrew Crumey, open-ended reflections that tickle the belly of life. "What we see is a very limited example of what there could be. It's always very interesting to ask the question, what if? I think it sheds a lot of light on how things work if you say, well, what other ways could it go, what are the alternatives?"

Chance and paradox are the touchstones of his work, direct pointers towards his scientific education. Brought up in Kirkintilloch, Andrew Crumey studied theoretical physics and mathematics at St Andrews and went on to do a PhD on nonlinear dynamics at Imperial College, London. He started research in the same field in Leeds but gave this up to concentrate on writing, and is now a maths teacher at a girls' school in Newcastle.

"I always knew that I was going to be a writer. I remember at school telling a teacher that I was going to do science till I was 30 and then I was going to be a writer. At that stage I didn't read anything, I didn't write anything, I just knew temperamentally that I was going to sit at a desk and dream things; I always knew that's what I was about, whether it was doing maths or writing novels." Which is perhaps why he likes to put distance between his fiction and his academic background: "There's a tendency to see me as a scientist. I don't. I see myself as a novelist. I don't see any great difference between what I'm doing and any other novelist is doing. It's about storytelling for me."

But each of his three novels bears the mark of the scientific brain: a delicate precision in language, structure and tone, a fascination with questions so huge they make your head throb, and a confidence to posit ideas that remain incalculable. It is plain that the reasons which made him go into research are those that lie behind his writing: "I liked big questions and big ideas." But they may also explain why he remains undeservedly neglected.

From critics he has received plaudits that would turn any new writer's head: "I predict that Andrew Crumey is going to be one of the major novelists," said Books in Scotland about his first novel, Music, in a Foreign Language, which won the Saltire Best First Book Award in 1994. Of his second novel, Pfitz, Jonathan Coe wrote in the Guardian: "At this rate Crumey may yet become a hero to fans of the postmodern Euro-novel who wonder why we Brits so seldom produce a home-grown variety." But praise and translations have not yet led to more popular success.

An immediately likeable man who combines an air of easy-going affability with unmistakable strength of will, Andrew Crumey sits on the fringe of the literary world, neither part of the great Scottish circle nor embraced by the British fold. He shrugs. "I get nice reviews but not a lot else. Gradually there are one or two people taking notice of what I am doing, but I have the feeling I've been underrated or undervalued."

His writing is at once refreshing and familiar. Characters and stories flit through the pages like scenes glimpsed from a train, effortlessly created and seductive in the way they hook the attention. Within a few paragraphs Crumey's great influences can be felt: Kundera, Voltaire, Marquez. There is an Enlightenment quality to his prose and the mannered but elegant phrasing.

Music, in a Foreign Language was a complex but highly readable work that questioned the nature of fiction as well as throwing open issues of morality and history: tricky subjects, handled with subtlety and an obvious pleasure. Pfitz, which followed, was less accessible, but nevertheless intriguing and, for all the questions it left frayed or unanswered, rather satisfying.

With his third novel, D'Alembert's Principle, Crumey hopes to attract more attention. Whether or not this is the book to bring him to the general public - I rather doubt that it is - it is certainly another beautifully composed work which lets you glide through the story but afterwards leaves you asking questions, looking for connections and puzzling, quite happily, for hours.

A tripartite novel, its central part is a piece of historical fiction, based on the mathematician Jean le Rond D'Alembert, Diderot's colleague on the great Encyclopedie. Lovingly recreating D'Alembert's life and tragic love for the saloniste, Julie D'Espinasse, through a fictional memoir, it elucidates D'Alembert's idea that the world can be reduced to basic principles, that everything can ultimately be explained by a Great Fact, much like today's Theory of Everything. Rather mournfully, D'Alembert states that he put his mind to discovering this single principle "so that I could then find some explanation for that question which has caused me more thought and fruitless deliberation than any problem of planetary motion; namely whether the actions of certain people towards me have been out of malice or out of kindness." In D'Alembert's case, the Great Fact of his life is not his genius or his generosity but his unrequited love for Julie. Only after her death, when he read her letters, did he discover she had all along been in love with another man.

For Crumey, D'Alembert is a fascinating figure, an outsider whose assiduity in trying to understand the universe is perhaps not dissimilar to his own. The second and third sections of the novel dramatically alter the book's tempo and elaborate D'Alembert's classification of life into Memory, Reason and Imagination with some great storytelling and a piece of 18th- century science fiction.

As with most novelists, all Crumey's work has a recognisable slant: "Ideas of chance are always going to be there as part of the philosophical furniture. So far I see what I'm doing as being as though I have a room and I'm taking things out of that room, so everything is coming from the same place." Yet despite the intellectual depth of his writing, he insists that his starting point is an image or a character: "I write because I'm fascinated by story: the mechanics of story, the way language creates something so you can see a picture in your head of a place, a person or an event, which is magical to me a I'm not interested in politics or society. I am interested in things like where did we all come from and where are we going?" Big questions from a man with big ideas who knows you can't get interesting answers unless you ask interesting questions.

The Journal (Newcastle). May 13, 2000.

A North-East author has followed in the footsteps of Salman Rushdie, AS Byatt, Ted Hughes and others in receiving an Arts Council writers' award. Andrew Crumey, a father of two from Jesmond, Newcastle, was presented with his £7,000 award by the Poet Laureate, Andrew Motion, in a ceremony at the Millennium Dome. "These awards buy you time," said the author, who became a full-time writer four years ago after working as a maths teacher in Gosforth. "I may use it to travel or to do some research for the next book. The money will certainly be useful." A quality linking all 15 writers who received the awards - inaugurated in 1965 - is that they have already demonstrated a significant talent. Andrew Crumey was born in Glasgow in 1961. He went to St Andrews University in Scotland and Imperial College, London, where he studied maths and theoretical physics. An interest in quantum theory, mathematical paradoxes and philosophy forms part of the background to his fiction. His first three novels - Music, In A Foreign Language [1994], Pfitz [1995] and D'Alembert's Principle [1996] - were published by the small publishing firm Dedalus. The fourth novel, Mr Mee, is published next Friday by the bigger Picador. The author describes it as "a comedy about Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Internet pornography and the delicate problems of growing older". Its hero is an 86-year-old book collector.

Simon Johnston. Herald & Post (Newcastle). May 24, 2000.

A city author has been presented with a prestigious national award at the Millennium Dome in Greenwich. Andrew Crumey was one of 15 authors from across the country who were presented with the £7,000 Arts Council Writers' Award by Poet Laureate Andrew Motion. Previous winners of the award include Salman Rushdie, AS Byatt and Ted Hughes. Andrew was delighted to pick up the award, which was given for a series of stories entitled Impossible Tales. This is not the first time his work has attracted literary acclaim. His second novel, Pfitz, was voted a 'notable book of the year' by no less than the New York Times. Until 1996, Andrew was a maths teacher at Westfield School in Newcastle. His fourth novel, Mr Mee, has just hit the bookstands and he hopes that this will further enhance his reputation. And the secret of Andrew's success? "Usually I just sit down and write without much research or planning," he said. "When I start a story I don't always know what the end will be." Despite the fact that he does little research and he is not a 'realist' writer, Andrew's work has been acclaimed for it's vivid portrayal of 18th Century life. He added: "I am not interested in minute historical detail such as how they buttoned their coats or what cigars they smoked. Instead I try to capture how the people of that time thought and felt."

Nicholas Wroe. The Guardian. July 21, 2001.

'The trouble with so much science in fiction is that the science is usually used as a metaphor," explains the novelist and literary editor Andrew Crumey. "All these wonderful ideas about DNA or black holes or artificial intelligence or whatever end up just as the background to a relationship between a couple of people in Hampstead. The science is hauled in to ennoble the characters. But I take the view that the science is a lot more interesting than a couple of people in Hampstead. In fact, it mostly makes the people seem insignificant by comparison."

As the holder of a PhD in theoretical physics, Crumey plainly knows what he is talking about, but says he was attracted to physics "not because I was crazy about calculating, but because I was interested in philosophy". His fourth novel, Mr Mee, reflects this approach. Like its predecessors, it contains its share of scientific content; however, in cleverly weaving together narrative strands from the 18th century and the present day, it is also a moving philosophical thriller that engages with a mysterious Enlightenment encyclopaedia as subtly as it does with the internet, taking in pornography and quantum mechanics on the way.

Crumey's interest in science goes back to his childhood, when he almost exclusively read encyclopaedias and science books instead of fiction. "It wasn't until I was in my mid-teens that I saw just what a novel could do. A teacher gave me Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, and for the first time I was more interested in what was in the book than in things in the world."

However, this revelation didn't alter his scientific trajectory. By the time he went to university, he still "had no interest in writing. I was your typical nerd: a reclusive, swotty scientist with negligible social skills and deplorable personal hygiene." But he read a lot for all that, and looking back he is glad not to have gone down "the English degree route. "I think I ended up reading the same quantity as someone who had," he explains, "but it was different stuff. I have great big gaps, but I have also read loads of things that are off the beaten track, like Borges and Calvino and Diderot, who have all been influential on my writing, and whom otherwise I might not have encountered."

Crumey was at the Leeds University maths department on a three-year research project when he wrote his first novel, Music, in a Foreign Language . It was written on an Amstrad computer, and was published in 1994. He has a theory - which sounds like the basis for someone else's PhD research - that the chapter lengths of novels written at this time tend to be around 10 pages because that was all an Amstrad could cope with.

The book drew heavily on the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics, which says that every time a choice presents itself, another universe comes into being. For instance, whenever you toss a coin, the universe splits into two - one in which the coin comes up heads and one in which it comes up tails. At the time of publication, Crumey was living a double life of his own, teaching maths and physics in a Newcastle school by day and writing at night.

The idea of multiple realities has subsequently run through all his books. He published his second novel, Pfitz, about the creation of a perfect city, in 1995, and followed it up the following year with D'Alembert's Principle, featuring the eponymous 18th-century mathematician.

At around the same time Crumey also launched a Scottish writers' website that quickly became one of the best literary resources on the net. "I got on to the net in the late 1980s," he explains. "It had a wonderful pioneering spirit, and the only other people on it were fellow nerds. When I started the site there wasn't much literature out there, and pretty soon I was getting emails from people basically asking me to write their essays or chase up some quote or other. When I started to get BBC researchers asking for information I thought: 'Hold on here, you're getting paid for this and I'm not.' I'd become this sort of authority just because it was on the web, but if I'd put it in a book no one would have been interested."

He has now withdrawn from the site, and says his enthusiasm for the internet has plummeted. "It's about as exciting as going into any high street, whereas it used to be like going to an interesting second hand bookshop. It just takes too much searching to find the little nooks and crannies that might be appealing. And I got fed up staring at a screen at work and at home."

Crumey works as the literary editor of the Scotland on Sunday for two days a week, allowing him the rest of his time to write. Mr Mee is the product of this new regimen and has been his most critically acclaimed book to date, being called in by last year's Booker prize panel. But while its critical success has been gratifying, Crumey, looking back to the start of his literary career, expresses a wry regret. "My publisher asked me to write a blurb for the cover of my first novel and, with extreme immodesty, I compared myself to Borges and Calvino. Ever since, the reviewers have compared me to Borges and Calvino. Interestingly, I didn't mention Diderot, who has been equally important, and not many other people have either. Thinking back now, I wonder if I missed a trick. Perhaps I should have mentioned Shakespeare and Tolstoy as well."

Evening Chronicle (Newcastle). March 31, 2006.

A theoretical physicist from Tyneside has been announced as the latest winner of the biggest literary prize in the UK, worth £60,000. A ceremony was held at the Baltic, in Gateshead, last night and Andrew Crumey, who is originally from Glasgow but has lived in Newcastle for 14 years, was unveiled as the winner of the Northern Rock Foundation's Writer's Award. The prize, which is only available to previously published authors living and working in the North East or Cumbria, allows the winner to give up the day job and write full time. The £60,000 is paid out in equal instalments over three years. Now in its fifth year, the award was last year presented to poet Gillian Allnutt, from Esh Winning, in County Durham. Previous winners were Anne Stevenson, Julia Darling and Tony Harrison. Andrew was described as one of Britain's most original writers, whose academic training in theoretical physics has provided rich material for his literary work. His previous novels Mobius Dick (2004) and Mr Mee (2000), among others, have already won praise and been shortlisted for the literary world's most prestigious awards and translated worldwide. Andrew said: "For the last six years, I've been juggling a part-time job as literary editor of Scotland on Sunday - commuting up from Newcastle to Edinburgh two days a week - along with writing my novels and helping to bring up two young children. Now I can concentrate all my working hours on writing, and I can also have more time for the things that make writing worthwhile, including being with my family."

Lindsay Jennings. The Northern Echo. March 31, 2006.

I'm not sure what to expect when I arrange to meet Andrew Crumey. He has a PhD in theoretical physics, is a former literary editor and he's just won Britain's largest literary prize - a whopping £60,000 - so he can give up the day job to focus on his writing. Are we going to end up chatting about the theory of relativity or the Big Bang theory? Yes, as it happens. When he answers the door of his Gosforth semi, Andrew is warm and welcoming and we move into the back room where a computer is giving off a luminous glare, a few lines dotted across the screen. Winning the Northern Rock Foundation Writer's Award means he can afford to focus on his writing full time. For the last six years he's been juggling his part-time job as literary editor of Scotland on Sunday, commuting up to Edinburgh two days a week, as well as trying to write and look after his two children with his wife, Mary.

Andrew, 44, was born in Glasgow to working class parents. He describes them as intelligent people with a "questioning attitude" to life which they passed on to their son. "I would question ideas and the way things were done," he says. "It gave me a slightly rebellious streak. In one sense I'm very conformist and suburban and banal but in an intellectual sense I'm a bit of a rebel." He recalls his grandmother reading him stories as a child and he loved writing and "making things up".

But, he ended up pursuing a career in science - the words of his English teacher that "there's no money in novel writing" no doubt ringing in his ears. He left St Andrew's University with a first class honours degree in mathematics and theoretical physics and studied for a PhD before eventually becoming a research associate at Leeds University. He went as "far in science as I wanted to go" and settled in Newcastle, teaching maths and physics at Westfield School in Gosforth. In between lessons he would scribble down bits and pieces.

His first offering, Music in a Foreign Language, was published in 1994 and won the prestigious Saltire First Book Award. He can still remember reading his first review. "There are various little moments that you cherish, like seeing it in print for the first time, but the real buzz was seeing it in a newspaper. It was only a tiny little review but it was really nice," he says. His subsequent books - Pfitz, D'Alembert's Principle, Mr Mee and Mobius Dick - have all garnered good reviews, the accolades ranging from making the Booker Prize longlist to numerous Book of the Year honours.

There was even an embarrassing moment when he was chosen as one of Granta's best young British novelists four years ago - only to be told that, at 41, he was a year over the qualifying age. "It was disappointing but at the same time funny. My publishers had entered me and I sort of disqualified myself. A lot of people said I should have lied about my age, but, you know..." he shrugs, philosophically.

"As a writer, you need these things in terms of getting exposure but if you take them too seriously then you're in trouble. Writing is a private, personal, intense thing and if you want to be able to do that you have to shut out all those things like awards and be true to what you're doing."

The book he's working on now, for which he received his Northern Rock award, is called Sputnik Caledonia and is about a young boy growing up in 1970s Scotland who embarks on a space mission. It melds quantum physics with telepathy and is the first novel he's written with a synopsis in mind. "With all my other novels I would write bits and pieces and they would connect together and usually have several threads," he says. "With this one I wanted something which was a bit simpler but with more complex ideas going on."

He admits none of his books are commercially orientated. "I write the books I want to write," he says. "Every writer sits down and writes the best they can do. If your interests are a bit esoterical, then OK you aren't going to please everybody, but there's still a lot of people who are going to be. With Sputnik Caledonia I want people to feel comfortable and not get too many shakes." He pauses, a rebellious look flitting across his blue eyes. "But I'll lure them in with a false sense of simplicity."

As you might expect from a scientist, he writes "very methodically", sitting down at 9am when the children have gone to school, until about 3pm. He loved his job as a literary editor but will love dedicating all his time to his novel even more. His books are a way of expressing his curiosity about the world, where the reader can learn one minute or be in the middle of a drama the next. "I'm interested in starting from the ideas and seeing what story comes from those ideas and how that becomes drama, that's my thing."

And what about aliens, I ask, possibly a little too abruptly. Does he believe there's something out there? "Yes, why not, I think there has to be, the universe is just so big," he says. "But the idea of higher intelligence, people were saying that in the 18th century. I suppose one thing is we tend to look at it in terms of consciousness, that there are aliens out there who think like us, but they could communicate without consciousness."

He says he would love to believe in time travel too, pointing out that we already have time travel into the future in the way in which we speed through time zones, so you can arrive somewhere younger than you were. The past bit is complicated and he highlights the 'killing your grandmother' paradox, whereby if you go back in time and kill your grandmother how can you be born?

"The only way it can happen is if the past is the same as the future," he says. "For time travel to be possible you have to be able to change the past and to do that there has to be lots of pasts which is where you end up with parallel universes." The other thing, he says, is to think that everything is fatalistic, so we believe we can change things, when in fact our lives are already pre-determined. "The problem with that is that Einstein's theory of relativity (which revolutionised the concept of space and time) says that, in principle, you can go into the past. What physics has concluded is that Einstein went wrong, that general relativity went wrong somewhere."

Andrew is an atheist and admits he is concerned at the way some schools teach creationism as the main theory behind how we came to be here. He compares teaching creationism alongside evolution with children being taught about the Holocaust alongside David Irving's book which denies that the Holocaust ever happened. "We would have mass protests if we did that," he says. "I think going in and saying here's creationism or here's evolution is making a very complex story simple and it's creating a false dichotomy for people and a lot of confusion."

Having been a literary editor, he's learned not to take the reviews too personally. "It's very tempting to think 'oh they've just got it in for me'," he laughs. "But that's not what it's about." It also gave him a good insight into the book world and if his career continues to be successful, he's not likely to fall for the hype. In his spare time, he loves being with his family and gazing at the stars through his telescope, wondering, no doubt, what's out there. In the meantime, he's not in any danger of disappearing into the clouds. His books are described as being a mixture of history, philosophy science and humour - a bit like him. He was fun to chat to. "Let's not take it too seriously," he smiles. "I think that's the moral of the story."

Scarlett Thomas. Independent on Sunday. April 9, 2006.

Andrew Crumey, the possessor of a PhD in theoretical physics and author of the hugely acclaimed novels Mobius Dick, Mr Mee, D'Alembert's Principle, Pfitz and Music, in a Foreign Language, has just won a huge prize for his writing. On the basis of some sample material from his work-in-progress, Sputnik Caledonia, a novel about quantum physics, telepathy, and a boy who embarks on a space mission, the Northern Rock Foundation has awarded him £60,000. The money is paid out over three years, and is intended to enable a previously published writer to live on a salary while doing a job that, as we all know, doesn't always pay the bills.

I call him up to congratulate him and he says, simply, "Thanks", and then asks about my writing. This is completely in character: Crumey is one of the most modest writers I've ever known. It turns out that we're writing about a lot of similar subjects. According to the synopsis of Sputnik Caledonia, Crumey is once again connecting theoretical physics with theories of the mind, although this time he's making a new connection with Marxism, and writing about a 1970s working-class, left-wing Scottish childhood not too far removed from his own.

I'm intrigued by the "psychophysics" mentioned in the synopsis and tell him that I've also got telepathy (of a sort) in my next novel. Before I know it, I've told him the whole plot. Embarrassed, I quickly make a joke.

"Hey," I say. "We should round up all the competition - all the other people writing about Schrödinger's Cat and the multiverse and the connection between matter and consciousness - and lock them in a room and not let them out."

Crumey laughs, clearly humouring me. "Er, yes." He's been researching Lenin's view of science and identifies himself as an anti-idealist materialist atheist. Perhaps he thinks I'm serious and there could be an actual room. Maybe there will be.

Enough of my lame jokes. What does the prize mean to him?

"Time, first and foremost," he replies. "And freedom. I'm obviously not a writer for the money, but this award means that I can write for three years without having to worry about making a living. Prizes also mean recognition, which is lovely. But the usual experience with prizes is not winning, so you develop a thick skin."

You do need a thick skin to write professionally. Not only is it all about not winning prizes, it's also about the disappointment of people not understanding your work (Crumey recalls thinking that everyone was going to understand his first novel. When they didn't, he realised that you sometimes have to make the connections "more obvious"), and being regularly described as "postmodern". Crumey is not a postmodern writer, however. Postmodern writing has little or no depth, but Crumey's work asks the biggest questions there are - and manages to connect political, scientific and philosophical ideas in a way that isn't possible for many people in a culture that seems keen to split these subjects into "disciplines". Crumey acknowledges that his fiction is about "finding things out", but when he claims it's for his own pleasure rather than for the benefit of humanity, I'm not convinced.

I suggest that perhaps we're all trying to get at the truth, and it doesn't matter if we approach the big questions using science, art or philosophy.

"It depends on the question you want to ask," Crumey says. "If you want to find out whether there's another planet beyond Pluto, you couldn't find out by writing a novel about it. The problems begin when you use, say, religion to ask questions about the origin of the universe. If you want to do science, you have to be able to test your results; you can't do the whole thing in your head."

Perhaps novelists just ask the questions, then, I say. Perhaps it isn't about answers. "What we do," he says, "is to create something autonomous without truth and falsehood. It's very different from what the scientists are doing. Mathematicians, for example, are constrained by logic."

I think that perhaps we are just as constrained by the limitations of our comedies and tragedies, still Aristotelian after all these years. But Crumey's novels don't actually follow these rules. The end of Mobius Dick has some comedy and some tragedy in it. Is this a paradox? I wouldn't be surprised. Crumey likes paradoxes.

"To me, a novel is made up; it is a fiction. But it's the paradox of being unreal and real at the same time that interests me. F Scott Fitzgerald talked about the importance of being able to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time. It's a very child-like way to be as well. Even as grown-ups we go to a magic show and we can be impressed by the illusion and we don't want to know how the trick is done. That's what novels are like."

As a physics undergraduate, Crumey became interested in Hugh Everett's Many Worlds interpretation of quantum physics: the idea that every probability exists in a parallel universe somewhere. First he treated it as "a joke"; then as "a fairy tale". It later became a key idea within Mobius Dick.

I tell him about the time I realised that if you go along with the Many Worlds interpretation, then every novel we write actually describes some reality out there in the multiverse. Nothing is fiction.

"Many Worlds theory is very much a thing of our time," he says. "The idea of alternatives, and this sense that anything should be possible for anyone."

Like the American Dream?

"Exactly. The capitalist dream. The film The Matrix is the ultimate realisation of the capitalist dream: the world is an illusion, but if you try hard enough you can beat it." Crumey then connects Many Worlds theory with DVD extras - which may give you some idea of the sort of novelist he is. "All the outtakes and deleted scenes... It's like a multiplicity of possible works," he says.

Psychophysics turns out to be just like the Many Worlds interpretation: he likes and dislikes it at the same time.

"Remote viewing; goat staring... It's all a bunch of hoaxes," he says. "I like all that stuff, but it's basically junk. You may as well imagine that we've got eyes on the ends of our fingers or something. In my novel I'm going to use psychophysics in an attempt to explore the material basis of consciousness... But I don't believe in any of it," he says, laughing.

I bet he does believe in it a little bit. There must be a parallel world out there with an Andrew Crumey who believes...

I tell him that I believed in the strange physics in my novel by the end, but he doesn't take the bait.

"Doublethink is what writing is all about," Crumey says. "You believe and you don't believe all at the same time. Everything is possible." He talks about Leibniz's view that we live in the best of all possible worlds. But for Leibniz, of course, it's the existence of God that guarantees this.

But in our postmodern world - or even the world of materialist atheism - there surely is no God?

"Well, that's too bad," says Crumey. And he laughs again and says he has to go and pick up his kids from school.

Lee Randall. The Scotsman. March 8, 2008.

As Sputnik Caledonia opens, we learn two things about its protagonist, Robbie Coyle: the nine-year-old still wets his bed, and he dreams of becoming an astronaut. By the satisfying end of a wickedly funny tale, we're in the company of a different young man known simply as "the kid". Also focused on the skies, he contemplates a plane that may or may not contain a grown-up Robbie Coyle, who may or may not be carrying a bomb, which may or may not detonate in mid-air. These images of flight are apt, for with this, his sixth novel, Andrew Crumey has crafted a tale that sends the heart soaring.

Fans (disclosure time - I'm not just a fan, but a longtime friend) reading that description may be chuckling with delight, reassured that the book revisits themes woven through all Crumey's books: multiple worlds, alternative narratives and meta-texts, and the thorny questions posed by physics and philosophy. But there's an extra dimension in the new novel - on the strength of whose opening chapters he won the GBP 60,000 Northern Rock Foundation award - that should capture him a wealth of new readers.

On a recent visit to his old stomping grounds - Crumey is the former literary editor of our sister paper, Scotland on Sunday - we caught up for a blether, and I pressed him about a comment from an e-mail, when he called this his most emotional book to date. How so?

"People said that earlier books had lots of interesting ideas, but the characters were a bit like chess pieces being moved around. I wanted a book that was more character-based and linear, a simpler, more traditional novel. When I say emotional, I mean something that makes an emotional impact that people respond to, rather than just reacting to with their brains."

The first section occurs in a town not unlike Kirkintilloch in the 1970s, which is, not coincidentally, the site and era of Crumey's childhood. It centres on the enchanting Coyle family: father Joe, a rabidly socialist Clydebank factory worker, mum Anne, given to unconsciously hilarious turns of phrase, Robbie and his sister Janet. This is a family given to weekend yomps and probing conversations about everything from politics to Aristotelian theory. How much of that is drawn from life?

"He's a kid of my generation, from the town where I come from, but Robbie Coyle isn't me, and his family isn't my family," he assures me. "Of course there are bits and pieces of my life in there. Yes, I did want to be an astronaut when I was a kid, though I never went into training like Robbie, or dressed up in a spacesuit. I had a Batman outfit, but that was different. And I did have a sleepless night once after someone suggested to me that my parents were aliens in disguise."

Sounding like the teacher he was, Crumey chides me that autobiographical titbits aren't absent from earlier novels, merely masked by their surroundings.

"I've written about people in different centuries, so you don't start out looking for the link between author and character. The classic quote is Flaubert, 'Madame Bovary, c'est moi.' I'm not sure if he really said it, but it's the idea that all your characters are you in one sense or another. In other books I've used voices I know from real life. Here it's more explicit. It's not the data, but the rhythms."

Crumey has said his books form a sequence that can be read in any order, but he did set out to make this one distinctive. "When people say after a certain number of books, 'Oh, he writes this kind of stuff, there's a devilish urge to do something different. I've done things like this before, but not published them. Most of what I write never sees the light of day, but it's there and potential material to draw on.

"If this novel is different, it's to the extent that it starts very much from voices. If you can hear a character talking in your head, that's what makes them alive and that was central, initially, more than plot or structure."

He'll often start writing unrelated bits and pieces, then examine them with a puzzle-builder's eye. "Where this book is like my others is that it's a collage of things that, superficially, are really different, almost disconcertingly so, like they shouldn't fit together. But the whole game is to make them fit together."

The ideas are here, as ever, just relegated to the background. "The first part is simple and episodic and, I hope, funny and enjoyable, but it can only go so far, then there has to be another level. The middle section is where all the story is and, to an extent, the ideas. It's coming from authorial voice rather than character voice. But I wanted this sense of connection, that there's some sort of mirror."

In this section we reconnect with Robbie, now 19 and living in the People's Republic of Britain, which emerged after the Nazi invasion during the Second World War. It's the society dad Joe might have dreamed of - had his dream of a workers' revolution turned into a nightmare. Robbie is part of a team training for a suicidal manned space flight to explore black holes. Crumey has had this vision of communist Britain before, but now it feels especially grim, especially for women.

He nods. "Soviet communism made slaves of everyone. I wanted to portray that, and I was conscious of wanting to write a book that would appeal to a female audience, one that would say something specific to a female reader.

"In a sense, that section uses repression of women to represent repression of people in general. You have this Kafkaesque set-up where people have to have sufficient freedom that the plot can happen, but at the same time you have to portray the slavery, so you need something to contrast it with.

"The slavery of the women is that contrast. The thing that ultimately makes Robbie rebel in that society is the way it treats women. No-one should think this is a nice place to live. It's based around brutalising people and divorcing them from their emotional connections."

This idea of mirrors plays out in the middle and final sections, where characters, motifs and settings recur, subtly skewed. "Everything is there but potentials are realised. All the material is there in the first bit of the novel, but things grow out of it in the middle and final sections. It's this idea of growth. The kid in the last bit is a destabilising force. I always tend to go towards the rational, and I wanted to push in the direction of the irrational in this book. Who is this Robbie Coyle? Is he a ghost? A spaceman?"

I'll leave that for readers to decide. But what I will tell you, what I've been telling everyone as I recommend Sputnik Caledonia, is this: as the novel drew to its close I felt my heart swelling with emotion. I can't remember the last time I was so reluctant to put a book down.

Questions from a blogger (2014)

Where did your devotion to writing come from?

When I was a kid I loved making up stories, whether in writing, drawing or role-play games. I’ve always been a dreamy, introspective sort of person, with a fair amount of determination to complete difficult challenges I set myself, so all of that predisposed and equipped me to be what I knew I would always end up being.

Please describe your journey to becoming a published author.

In my twenties I tried planning a novel in great detail and as soon as I started writing it I found the characters were like bad actors. That was lesson one: don’t plan, improvise. I joined a writing group, which gave me encouragement, and after doing lots of little stories I hit on one that kept going and became a novel. I bought The Writers’ And Artists’ Yearbook and followed the advice given there about approaching publishers. The fourth one I tried said yes.

What would you say to someone who has ‘always wanted to write’ but is too nervous to begin?

I would ask: what are you afraid of? Many people say that lack of time is the barrier, but maybe that’s another way of expressing nervousness about starting. The worst that can happen is that you find you’re not very good at it, so accept that possibility and give it a go. I was rubbish at skiing but I’m glad I tried.

What is the best piece of advice about writing you can offer?

Think about the reader.

And the worst advice you’ve received?

Think about the market.

Are there ways in which the publishing industry has changed since your first book was published?

A lot has changed in 20 years but the fundamentals are the same. If a book is good then someone, somewhere will publish it eventually, and it might even get read by a few people. If a book is bad it still might do all of those things. 20 years ago there were a lot of publishing houses that have all now been swallowed up by conglomerates, and meanwhile a lot of new small, independent publishers have appeared. There are also a number of independent publishers that have survived the whole time by sticking to their values and not trying to chase every latest trend. Dedalus is one such publisher, they’ve supported me wonderfully over the years, and I’m very happy to be with them.

What would you recommend writers do to get themselves and their work noticed?

Concentrate on quality and eventually you will be noticed by people who appreciate quality. Concentrate on PR and you’ll look like just another jerk.

And what advice would you give to those receiving rejection letters?

Get used to it. Be patient. Don’t give up. Get on with your next book.

How important is it to join a writing group or find people who will honestly critique your work?

It worked for me.

What is your favourite line from any book?

I’m not good at remembering lines (even from my own books).

And finally…there is this squirrel who sits on my garden fence and stares at me through the window. I think he means me harm. What would you do?

Learn Squirrel.

Questions from Spain (October 2009)

1. When and why and how did you start to write with a literary purpose?

As a boy I knew I wanted to become a writer, but I had various false starts and it wasn't until my late twenties that I began seriously.

2. What do you want to tell when you decide to write?

What I want is to discover. A finished novel is the result of the process of discovery. I start with ideas, but they are only a beginning, not a goal.

3. Which is the way you usually take to write, the techniques you use, the face you want to give to your texts?

There is no starting point. Small ideas begin to connect in some way. These may or may not grow into a novel-length draft. Once I have a work of that size, I then know what sort of questions I am asking, and can start again. So my novels undergo very extensive reshaping and rewriting.

4. Creative process: before the seed of a new story or poem, do you prefer that it grows inside your heart and mind before writing it on paper or maybe do you write it from the first signs and then allow that it drags you forward?

For me it all has to happen outside my head, on the computer screen. Otherwise it is not writing. What happens usefully inside my head is mostly subconscious, and I try not to interfere too much with that. If I try writing inside my head then it ends up never going onto paper. Writing, for me, should feel like reading: it should make me feel surprised and engaged.

5. Study, learning and development of literary skills and techniques? Spontaneity and writing by ear? Which option do you prefer?

I believe that spontaneity in art can only produce interesting and original results if there is a grounding of technique, though technique can be acquired intuitively. It all comes down to reading a lot and writing a lot.

6. How "passion" can be recognized within a text? How a "cold" or "cerebral" -in appearance- text can be injected with passion? Is passion necessary? Where and how can we find the border not to be crossed?

For "passion" we could substitute many other words: voice, character, plot.... How is anything recognised in a text? That's the game of illusion that we play. Diderot proposed the famous "paradox of the actor": the best actor is not the one with most passion, but the one best able to fake it.

The question of how "cold" text becomes injected with life: this has much to do with the sensitivity of the reader. The reader is like the performer of a score. There is a big difference in appearance between a score of Bach and a score of Chopin - but both can be done with great expression, if the reader is sufficiently sensitive and alert to what the marks on the page mean.

7. In what circumstances the self-censorship (or the external censorship) can be necessary or useful for an author?

There is always a balance between urge and inhibition in everything we do. It can be fruitful or stifling. We just have to find our own balance. I would say, though, that I am far more risk-averse in real life than in my writing.

8. Do you wait for a reader or the fact that someone can read your texts is a secondary purpose? Do you think you must make easier your texts for the future reader or that reader must face alone the possible difficulties of the texts?

Writing is like having a theatre inside your head. You've got the stage where you make certain actions take place - but you've also got rows of seats with people watching. You have to think of every part of the theatre. Writing is a communicative act, but in a virtual sense. Reading a book, we imagine the author who is telling us the story. Writing one, you imagine some kind of reader. For me it's not a real person or a single individual or even a certain type of person. But I always have a sense of a reader, and I am always concerned with what (I think) they will know, what they will feel, what they will anticipate - and how I ought to show this on the page.

9. How do you define yourself as an author (style, worries, horizon, projects, genres you prefer...)?

I write philosophical novels, meaning that they ask questions and in this way seek to create a form of knowledge. Not conceptual knowledge, like a research paper, but artistic knowledge. I think that a great many novels could be considered philosophical in this sense, though their creators wouldn't necessarily think of them in those terms.

10. In the presence of a creative block, what kind of solutions do you take?

If something isn't working then I stop and do something else. The problem will work itself out in time, in the subconscious. I have periods of frustration and inactivity but they always pass. I am always "working on a novel", there is always a "work in progress". Before finishing one novel I am thinking about the next one, and I don't take any break in between. I also discard a very large proportion of what I write.

11. Open question: if you want, include here what you would like to say according to your experiences as a writer if it is not gathered among the previous questions.

I would only say that every writer I encounter is unique and has their own way of approaching or articulating the problem of writing. This is part of what makes it such a fascinating activity.

Questions from British Science Fiction Association (June 2009)

1. Do you consider yourself a writer of science fiction and/or fantasy?

No, but I have no objection to being considered one by people more knowledgable of the genre than I am. I consider myself a writer of philosophical fiction.

2. What is it about your work that makes it fit into these categories?

I imagine it is predominantly the content (which is sometimes manifestly scientific), and perhaps my professional background as a physicist. I have been influenced by philosophical ideas that are frequently used in speculative fiction (e.g. the plurality of worlds), and reflect upon them in my work. My literary influences have included writers (such as Borges and Orwell) often considered to have contributed to the genre.

3. Why have you chosen to write science fiction or fantasy?

I have chosen only to write novels that interest me. The choice of genre is one made by readers, and they are entitled to it.

4. Do you consider there is anything distinctively British about your work, and if so what is it?

I don't know what "distinctively British" means. My work has at one time or another been compared to Sterne and Orwell, both of whom were British, though I don't know if they were "distinctively" so. Equally, since Sterne was Irish and Orwell ultimately chose to live in Scotland (and since I was born in Scotland), I might be called "distinctively Celtic". National identifications are ultimately political and economic rather than artistic. As a way of extracting meaning from art I find them reductive.

5. Do British settings play a major part in your work, and if so, why (or why not)?

I've written novels set wholly or partly in Scotland, England, France, Germany, Italy, and probably other places I've forgotten about. Foreign settings have been influenced by interest in particular writers (e.g. Rousseau, Proust, Goethe). English settings are influenced by my familiarity with the country. Scottish settings are influenced by my having grown up there, by my relationship to the concept of "Scottishness" as a generic/political classification, and by the particular political history of that country.

6. What do you consider are the major influences on your work?

Other than the usual ones (autobiography, chance), the most important is the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, which I consider as significant an idea for our era as natural selection was for the nineteenth century. (I do not consider cultural importance equal to scientific truth; that's a separate question). The most important literary influence is Goethe, who was of course a scientist as well as an artist. His novel Elective Affinities takes a particular scientific theory as framing metaphor for a drama of human relationships: a paradigm for many subsequent novels, particularly in recent times, among which some of my own might be included. The major ideological influence is the opposition between socialism and capitalism. The major creative influence is music: I am interested in finding ways of responding to E.M. Forster's question, what a novel would be like if it was like Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

7. Do you detect a different response to your science fiction/fantasy between publishers in Britain and America (or elsewhere)?

Publishers and bookshops don't market my work as science fiction in any country, as far as I can tell, though some reviewers call it science fiction. I do better in some countries than others; I put this down to statistical variance. Some places you get lucky, others you don't.

8. Do you detect a different response to your science fiction/fantasy between the public in Britain and America (or elsewhere)?

Members of the public are individuals and respond accordingly: I can't draw any useful generalisations. The response I've noticed from science fiction critics in both Britain and America tends to be negative: when my work is viewed as science fiction it is often found not up to scratch. In that case I can only conclude that either I write bad science fiction, or else I don't write science fiction at all. When my work has been analysed according to standards of "Britishness" or "Scottishness", similar results have often been obtained. I once had my work reviewed as detective fiction, and again it was found wanting.

9. What effect should good science fiction or fantasy have upon the reader?

For it to feel good to the reader, it should have whatever effect the reader is seeking. As a writer I concern myself with stimulus more than response. I try to design the stimulus so that it will produce in the responder a free desire for repetition: something I would define as pleasure.

10. What do you consider the most significant weakness in science fiction and fantasy as a genre?

The weakness of any genre is its genericity.

11. What do you think have been the most significant developments in British science fiction and fantasy over the past twenty years?

I don't feel qualified to say. In literature as a whole, I would say the only measurable development is the passage of time.

Questions from Asylum.com (February 2008)

1. You're probably sick of being introduced as the ex-physicist novelist who won the Northern Rock Foundation Writer's Award. But can you explain what effect this had on your approach to your writing? And how come, with no day job any more, it still took you four years to write the book?

I don't get sick of being labelled as a scientist-writer: it's better to be labelled as something than not to be known at all, even if the label can be a bit limiting. But I don't know if being a scientist made me a certain kind of writer, or if being a certain kind of person made me become first a scientist and then a writer. Really I'm interested in philosophy: questions like "what can we know?" and "how does this affect the way we live?". I write philosophical novels. As to timing, I seem to have got into a pattern of one novel every four years, but that's partly because I throw away most of what I write, and much of what isn't discarded gets stored for later use, once the right time comes. Robbie Coyle, the hero of Sputnik Caledonia, first came to me about ten years ago, and I knew I wanted his story to turn into a kind of parallel-world space mission, but somehow all the ingredients weren't there until after I'd written Mr Mee, Mobius Dick, and some other books that didn't work out. Once I got going on Sputnik Caledonia it actually only took a year to write - the quickest I've written anything, even though it's my longest book. Somehow its moment had come.

2. Sputnik Caledonia is (a little) more linear than some of your previous books, and each of the three parts has a very different tone. Was this a conscious decision to break with the earlier structures, or did it develop as the book was written?

Yes, it was a conscious decision. Usually I let my books grow in a completely organic way, with no prior planning, but Sputnik Caledonia was a little more planned. What I didn't know was what would happen after the second part. The problem is that you've got two stories in two different worlds that both need to be resolved somehow, and for a while I tried making it a four-part book. Then I remembered the good-old Hegelian pattern of thesis/antithesis/synthesis: what I needed was a finale that would somehow unite both the earlier movements, and I do this with the aid of a new character, a new theme. It took a lot of trial and error but it was fun to do.

3. Your novels are always strong on ideas, but Sputnik Caledonia seems to have 'real' characters at its heart as never before: for example, the character of Robbie's father develops significantly - and heartbreakingly - through the course of the book. The scenes of growing up in 1970s Scotland are bound to attract suggestions of autobiography. Is there any truth in this? Where do you place greatest emphasis in the books you write (and read): characters, style, story, ideas?

It's true that when I was a kid I wanted to be an astronaut, and my dad was a very active trade unionist and committed socialist. But writing is about making things up, and what I admire most in novels I read is their inventiveness, the way they turn life into something specifically fictional. Proust is the greatest example of this: his novel reads like the memoir of a man who falls in love with the wrong woman, when in reality Proust was gay. In a novel, everything gets turned on its head (the great Russian theorist Bakhtin called this "carnivalisation"). And we read novels with a double-view: we know it's made up but treat it as if it were real. If we're pushed too much in one direction or the other then this magical double-view falls apart, the illusion is shattered. It's like looking at a painting: you know it's chemicals on canvas but it's also a landscape, people, houses. So this is where the emphasis lies in my writing: holding two completely opposite and contradictory views in mind simultaneously. Two worlds: one like our own reality and another that's a sort of parallel universe. In a sense, every novel is like that, the story of an alternative reality, though not every novel makes this doubling an explicit part of the structure. And how is it done? Through voices, events, people: the eternal stuff of fiction.

4. Part of Sputnik Caledonia is set in the British Democratic Republic, an alternate Britain where the Communist Party was elected after the Second World War. It also featured in Mobius Dick and Music, In a Foreign Language. Is there something you're trying to tell us?

Two things got me into my parallel world. One was learning, as a student, about Hugh Everett's "many worlds" interpretation of quantum mechanics, which is the basis for current thinking on multiple realities. The other was a research trip I made to Poland just after the fall of communism. The physics institute I worked in had until recently been the local Party headquarters, and was still full of relics of that time. The only way I could write about it was by translating it into a world I knew: Britain. That's how Music, In A Foreign Language got written. Now on one level this was all a kind of aesthetic decision, in the way I described in my answer to your previous question, but you have to realise that aesthetic theory is something you only come up with after the event: you write a book, then you wonder what question your book has answered. Once I began to understand parallel worlds as an aesthetic phenomenon, I was able to write Mobius Dick. But that still left me wondering about the psychological impulse that must have existed from the outset, and I knew this was related to the kind of socialistic upbringing I had, in which there was a kind of glorification of communism and a corresponding despising of capitalism. So, having written Sputnik Caledonia, I can see that one of the questions it answers for me is: why did I feel this strange romantic attraction towards a terrible totalitarian regime? For the reader, of course, completely separate questions get raised, the most arresting being, I hope "what happens next?".

5. Your first publishers, Dedalus, have been in the news recently as they've had their Arts Council funding cut. This conjures up horrible images of a parallel universe where Andrew Crumey never got published. At the same time we have more prizes, book clubs and blogs than ever before. What do you feel about the prospects for less commercial fiction today?

The situation with Dedalus is very sad and depressing, and also rather mystifying: other small publishers threatened with funding cuts won full or partial reprieves, and Dedalus seems to have been singled out for specially punitive treatment. They worked tremendously hard for me and still hold the rights to my first three books, for which they continue to find new markets - recently I began to be published in Hungary, Romania and Turkey, thanks to their on-going efforts. It would be nice if some day my backlist could go up in value and earn Dedalus some more money. Of course, for that to happen, I'd need to win some high-profile prize that would make me a more marketable commodity. How do I feel about all that? It's quite simple: writing is an art, publishing is a business, and I concentrate on the art, leaving business people to do the stuff that they're good at and I'm not. The prospect for less commercial fiction is as poor today as it was in the days of Joseph Conrad - that's life. If you want to be rich and famous then be a pop star or a TV chef. When I was a theoretical physicist I wrote papers that would be read by maybe a few tens or hundreds of people. I'm delighted that I've gone up a few orders of magnitude since then. Apart from the 3-year award I've been living on, I earn an honest crust through book reviewing and teaching creative writing. I wouldn't want to be wholly reliant on writing for my income: I know people who have to get their next novel done so they can pay their mortgage, and that's not my idea of fun.

6. Your books try to encourage the reader to hold differing ideas in their head at the same time, and yet your scientific background suggestions an attraction to solid facts, and 'truth' as a quantifiable quality. Is this something you enjoy playing with in your fiction?

I've already said something about this holding of different ideas in an aesthetic context, and it's time we gave it a name, which is "irony". In the original ancient Greek sense it meant "feigned ignorance", in other words it's what the character Socrates does in the dialogues written by Plato. Socrates says to people, "what does goodness mean?", like he has no idea, and in this way he teases out the problem of defining what it means to be good. Now that's pretty much what scientists do: they might say for example (if they're Isaac Newton), "why doesn't the Moon fall down on our heads?", or like Einstein they might say, "what happens if I travel at the speed of light". There were perfectly good answers to those questions at the time, just as there are dictionary definitions of "goodness", but the answers weren't good enough for Newton or Einstein. So science is fundamentally ironic: it's about believing and not believing something at the same time. This isn't my idea: it's my interpretation of what Goethe said in the early eighteen hundreds, and Goethe certainly knew a lot about both art and science. It's also pretty much what Bakhtin said about novels: they are all essentially ironic. In fact Bakhtin called the Socratic dialogues the first novels, and I agree with him on that. They raise questions for which there can be no single answer. The illusion that many people have about science is that it is somehow different: the term "law of nature" suggests a rule book written in advance, which can never be changed. Really all there exists is a "court of nature", where judgments are made according to the best available evidence at the time. No case is ever closed.

7. Finally, one of the pleasures of your books are the references to lesser-known works of literature which you clearly hold in fond regard, such as Hoffmann's Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr. If you ruled an alternate world, which one overlooked book would you make compulsory reading?

I would never make any book compulsory: rather, I would make some books forbidden, in order to ensure that people would read them. I'm delighted that Mobius Dick has helped boost interest in Hoffmann's Tomcat Murr (which was apparently Kafka's favourite novel). I hope that Sputnik Caledonia will do the same thing for Goethe's Wilhelm Meister, a great classic which tends to be unjustly neglected by British readers. I first got to know it as a teenager, through Schubert's settings of its songs - I re-read it when trying to figure out how to end Sputnik Caledonia, and it showed me the way. Two other books, which I came to for the first time only recently, have excited me with equal passion. One is Problems Of Dostoevsky's Poetics by Mikhail Bakhtin, whom I've mentioned a few times. The other is Monadology by Leibniz: a very short work that deals with the problem of space and time in a profound way. I suspect that the answer to quantum gravity lies in that little book, if only some smart young physicist can work out how to find it, and I only wish I'd read it when I was young enough to have a go. Putting it briefly, Leibniz's answer is that space and time do not exist: we only think they do.

Questions from Spain (November 2006)

1. Was it hard to make all the theories you explain in the book accessible for the general reader? Why is it that scientists are usually so cryptic?

Making difficult ideas accessible is something I try very hard to do. Leibniz said that if you can't explain something in clear, simple language then it means you haven't really understood it. By trying to express ourselves simply, we force ourselves to think. Language should be about communication, not mystification. Scientists can indeed be cryptic, but so can people in every trade, because special tools require special names; this is equally true of tools of the hand or tools of the mind. But even if those tools are unfamiliar to us, a skilled craftsman should be able to explain their use.

2. Does Mobius Dick have a happy or a sad ending? How did you come up with the idea for this book? How long did it take you to write it? Are you happy with it? What is the best and the worst about it?

Mobius Dick is both comic and tragic, because this is how I view life. The ideas came to me in separate pieces, and gradually I understood that they were part of a single idea: the appeal of the book is the way in which all its parts are gradually seen by the reader to be interconnected, because this again is how I see the world - as an interconnected whole, where any small part shows you something of the totality, like fragments of a hologram. I wrote many versions of the book over a period of about four years, but most of what appears in the final published version was written over a period of about a year. It is not a book that will appeal to everyone, because no work of art has that quality, except perhaps the most banal. The book's richness and subtlety will appeal to readers who like books that stretch and exercise the mind; the humour will appeal to those who can appreciate British irony; the thriller plot will please those who prefer a fast pace to a slow one. I don't know of any other book that is quite like Mobius Dick, and I feel proud of that. Its uniqueness is what readers will find either its best or worst feature, according to their own taste.

3. What do you answer when people ask "what do you do for a living"? Are you more a writer than you are a scientist? How interested are you in other fields, such as philosophy?

My livelihood comes from a very generous prize I won recently, which allows me to write anything I want. This of course is every writer's dream, and I feel supremely lucky. I also feel a responsibility to produce good writing so as to repay the generosity I have been shown.

I consider myself a writer because the part of the day that I call work consists of sitting at my computer typing words. But those words might be about science or philosophy or fictional people, and of course the same was true, for example, of Plato or Galileo, who could be considered scientists, philosophers or literary writers. I don't like barriers and labels: the way we earn a living is not what we are. I'm a human being who happens to write and think, but I do many other things too. The most important thing is my family - writing comes second and earning a living comes third.

4. Would you consider yourself a paranoid? Do you believe in conspiracy theories? What do you think of the term "conspiranoia"? Do you think books can actually make a change? What do you think it would take to "right the wrongs" in this world?

Not paranoid, only neurotic - though less than many other writers I know. I am fascinated by conspiracy theories, pseudo-science, crank ideas and so on. They form a kind of parallel knowledge system, helping us to understand how "mainstream" knowledge works.

Books cannot change the world - only people can do that. And the only thing that any of us can change is ourself. But by changing ourself we change the world, even if only by a tiny amount. I have read books that have changed the way I think, and perhaps I can have a similar influence on other people - but that is for them to decide.

5. What books would be included in your "Best ten books in History" list? Have you got any favourite writer? Are you a comic fan?

Some books I love: Goethe: Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship; Cervantes: Don Quixote; Proust: In Search Of Lost Time; Flaubert: Bouvard and Pecuchet; Diderot: Jacques The Fatalist; Dickens: Pickwick Papers; Montaigne: Essays.

I am not really a visual person: books appeal to me through ways other than sight. So among my list of books I would also include the 32 piano sonatas of Beethoven (plus the Diabelli Variations if they could be bound into the same copy).

6. Are you planning a next book? If you are, can you tell me about it?

I am nearly finished a new novel about a young boy who wants to be an astronaut, and finds himself launched into a fantasy world where he is to participate in a mission to a black hole. Like Mobius Dick, it is a mixture of the comic and tragic, involving ideas of science, history, politics, philosophy - but it is also different in many ways.

I am also researching a book about writers who have been interested in science - there are many examples. And I plan to write a novel about Beethoven. All of this will keep me busy for the next three or four years.

7. What questions would you really like to answer in an interview?

What I like most are unexpected questions - and I am gratified that I get asked so many different things by different people. Some want to know about science or philosophy or literature; some are interested in my life or my opinions. Rightly or wrongly, my books seem to persuade people that I have something interesting to say - and this must mean that my books have the sort of richness I wish for them.

Questions from a Spanish newspaper (October 2006)

1.- Una típica serie de peguntas que con seguridad le habrán formulado en múltiples ocasiones para empezar: ¿Cómo un profesor de física teórica se convierte en escritor de ciencia-ficción? ¿Y cuál de las dos facetas es más "fácil"?, ¿y más gratificante?, ¿y con cuál se gana uno mejor la vida? (A popular question that you have received multiple times: How does it is possible that a theory physics teacher, has become a science - fiction writer? Which of both activities are easier for you? and which one more enjoyable? And which one it allows you to live?)Every writer starts by doing something else, and with me it happened to be physics. Writing involves sitting at a desk trying to think of good ideas, and theoretical physics is much the same. But writing comes more easily to me, and gives me a chance to communicate with a wider audience. As for earning a living, this is always difficult for a writer. I had the good fortune this year to win a large prize that frees me from financial worries for the next few years.

2.- ¿Escritor de ciencia-ficción o de física teórica-ficción? Es decir, ¿hasta que punto su formación académica determina los argumentos de sus relatos? ¿Se ha planteado alguna vez trabajar sobre argumentos de "otra ciencia"-ficción? (How would you define yourself? Science - fiction writer or physics theory fiction? So, at what level, your studies background determinates the story of your books? Have you ever think about the possibility to write about the "other fiction - science"?)

I'm a novelist, pure and simple. I write about things that interest me, and that I hope will interest other people. In the case of Mobius Dick, this means things such as quantum theory, history, literature, music, technology. I've also written novels set in the eighteenth century, or in modern Scotland, or in alternative worlds. So I don't worry about defining myself - I leave categorisation to other people, if it helps them.

3.-Al hilo de lo anterior: ¿Cómo nacen las ideas para sus novelas? ¿Surge como consecuencia de la investigación o área en la que trabaja en cada momento o bien surgen de forma independiente, como pensamientos paralelos a su labor científica? (Following the previous point: How do the ideas of your novels came through? Does it is a consequence of your investigations that you develop diary, or are coming in a independent way, such as parallels ideas at your scientific activity?)

I write every day, and I start from random ideas. They might come from things I think about or read, or from places or people that strike me as interesting. Then out of these random pieces I slowly build up a story. I don't consciously "research" a novel: I prefer to let information sink deeply into my mind, then it can resurface in its own way.

4.- ¿Cree que algún día sus historias dejarán de ser ciencia-ficción para pasar a ser consideradas como novelas premonitorias o visionarias en el sentido de que anticiparon una realidad futura? ¿Cuándo estima que llegará ese momento en el caso de Mobius Dick? (Do you think that one day your books will be considered visionary novels in spite of science fiction? On the way that it will alert about a future reality? When do you think it will happens on the case of Mobius Dick?)

I will only be considered visionary if I make predictions which happen to be correct, and that is a matter of luck I shall leave posterity to mull over. What I write about is the world we live in now, and the habits of thought we all have, without even noticing. Fifty years from now we might have quantum computers on our desktop, and Mobius Dick might seem very quaint to anyone who should read it then. But I hope that if anyone happens to pick up my book in the future, they will find things in it that remain worth reading.

5.- Mobius Dick está plagado, desde el principio, de referencias a escritores y sus obras: desde Melville a Thomas Mann ¿Qué autores le han influido más? (Mobius Dick is full, since the beginning of references a writers and his novels: since Melville to Thomas Mann. What authors influent you more?)

When I was a teenager I read George Orwell, and he is a big influence, through his combination of the visionary and the political. I also loved Kafka and Goethe. Their writing is very pure, simple in style but perplexing in content. They are philosophical writers offering very different messages: with Goethe it is hope and with Kafka it is despair. And I love Cervantes, Dickens, Proust - all great humorists.

6.- Y por supuesto, Mobius Dick también está repleto de alusiones a muchos de los más famosos físicos de la historia. ¿Siente especial inclinación por alguno?, ¿Cuál es, si se me permite la expresión, "su héroe" en la física? (Mobius Dick is full of references to famous physics around the history. Do you feel an special opinion for any in particular? Which would be your hero?)

My hero from an early age was Einstein, and I still feel his achievement is of a unique kind. I put Newton in the same league, and all physicists would agree with that - but I also have a very special respect for Aristotle, and for Leibniz. They are under-rated by modern physicists, but I think that Leibniz in particular has much to teach present-day workers in superstring theory and quantum gravity.

7.- La novela plantea la cuestión de si los acontecimientos suceden por azar o si, por el contrario, existe un esquema lógico que lo conecta todo. ¿Realmente considera la existencia de dicho esquema? ¿Y que papel jugaría entonces la cuántica en esa visión? (The book is proposing the question if the events are happening by curiosity or if by the way, exist a logical structure that connects everything. Do you really believe on the existence of this structure? And what would be the rol of the quantium on this vision?)

This is a question that philosophers have puzzled over for millennia: is life a matter of chance or necessity? I agree with Engels, who saw the dichotomy as a false one, and modern physics supports this view. The laws of nature can be deterministic, meaning that the future is in some sense already settled - but the only device capable of predicting the future exactly is the universe itself, which we can regard as being, in effect, a quantum computer.